My Linguistic Autobiography

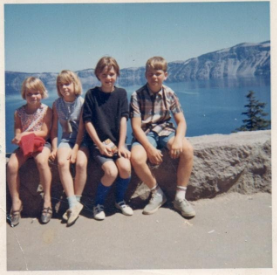

I grew up in rural, southern Oregon during the 1960s and 70s with four other brothers and sisters. My dad established a small medical practice there with my mom who was a registered nurse. Both my parents had grown up in the Midwest.

My mom’s family was Danish and had settled in Iowa to become farmers, and my dad came from a working class neighborhood in Detroit. After World War II, the GI bill was the ticket for him to break away from his working class upbringing and go to medical school.

My earliest linguistic memories began when I started school. There I became acutely aware that if I wanted to avoid ridicule it would be best not to sound too “educated.” I knew that my friends had a different way of speaking and I was careful to blend in. Some of the self-censored words were medical terms used by my parents, such as “axila” for “armpit,” but others were from my mother’s speech. For example, my mother, and consequently, I would pronounce “drawer” like “draw-er” a two syllable word.

My classmates let me know that this was not only funny, but quite wrong. I also remember silently correcting my teachers’ grammar while sitting at my school desk. I’m not sure why I did this. I don’t particularly remember my parents correcting our grammar except for my dad’s one pet peeve–that we say “kinds,” (plural, we were told), not “these kind of things.” My mother, however, would insist that we enunciate our words and would point out their orthographic features: “patriarchal” spelled “i-ar” not to be pronounced, “patri-ar-ti-chal,” and “ambulance” pronounced, “am-byoo-lance,” not “am-bee-lunce.”

As an adult, I became interested in second language acquisition because of my husband’s work that brought our family to Spain. I became obsessed with learning Spanish and spent every spare moment memorizing words and grammar. Learning a second language in country was a mixed experience, however.

On the one hand, it was comforting to learn to speak all over again in a new context where I was free to make mistakes because I was a beginner. On the other, it became clear how much language was tied to identity. Lack of language proficiency resulted in the loss of any previously held cultural capital I once held. My bachelor’s degree meant nothing to the street vendor selling vegetables; I just appeared to be lacking social skills.

During the course of our seven-year stay in Spain, we put our daughters in the Spanish school system. This was a complete immersion experience for them because the teachers, and students, did not know English. I began to notice interesting stages in their Spanish language acquisition. First, they would play with their toys, making up their own language comprised of Spanish sounds. Next, I noticed real Spanish words mixed with English in the same sentence. This evolved into full Spanish sentences that were not grammatically correct. But after three years in the Spanish school system our daughters were mistaken for Andalucían children and could translate from Spanish to English.

I also became increasingly aware of how different our daughters’ process of second language acquisition was compared to mine. They spent hours each day totally immersed in the Spanish school system and playing with their Spanish-speaking friends, whereas I shopped in Spanish and studied from books at home.

Their pronunciation was colloquial; mine was the textbook version. They began to speak with Andalucían intonations as a natural outcome of play; I was consciously aware of making intonations happen. Nevertheless, one day I found it strangely satisfying when I was mistaken for a French woman speaking Spanish rather than a U.S. Spanish speaker. Then, more often than not, I began to be mistaken for French. I was glad that I had somehow erased my United States identity by my pronunciation.

I attribute this willingness to shed my U.S. identity to two reasons. First, we were living in Spain when the United States was beginning to fall from global favor because of its political dealings in the Middle East. I held opposing political views and expressly did not want to represent the United States government. Second, this was my first extended stay out of country and I was going through a process of intercultural development from mono-cultural toward a more global worldview. As one’s intercultural experiences become increasingly complex it is not uncommon to emerge from a defensive polarized cultural orientation and begin to make sense of cultural differences by attributing positive evaluations to the other culture (Hammer, 2010). As I became more linguistically and culturally competent in Spain, however, this reversal orientation gave way to a deeper acceptance of my own cultural patterns as well as the cultural patterns of the Spaniards.

Eventually my love of the Spanish language and my interest in language acquisition led me to post baccalaureate work in Spanish, certification in secondary education and later, National Board Certification in world languages. After seven years in Spain, we moved to the South (in the United States) and my husband and I began teaching high school in a rural community outside of Charlotte, North Carolina.

Even though we had lived in several different regions of the United States and overseas, our extensive travel experience left us unprepared for the linguistic culture shock that we experienced there. The first thing we noticed was the Southern dialect. In the beginning, I thought it was soft and friendly, and indeed, people where we lived loved to strike up a conversation. I could also tell that there were different Southern dialects, but my untrained ear could not identify distinguishing features. My husband and I, however, were soon faced with what we considered a dilemma. We did not want our kids to pick up a Southern accent because we knew that the dialect was stigmatized in other regions of the United States.

But more important, I did not want them to pick up what I considered to be bad grammar. I found it especially irritating to hear teachers and the principal speak “incorrectly” over the intercom or in faculty meetings with phrases that included non-standardized features, such as, “We just don’t have no choice” or “We was hoping for more.” My rationale was that we were educators, so we needed to speak as though we were educated. Even though I knew that my colleagues and principal were not unintelligent, I could not help but feel that the stereotypes of the slow moving, slow thinking Southerner that I had seen portrayed in the movies were correct.

Notwithstanding my personal experience in Spain, where I wrestled with my identity amidst second language acquisition, I was unable to transfer this experience to the language variation of my students because they spoke English. It did not occur to me that they too might be struggling with their identity. Indeed, it wasn’t uncommon to run across Southerners who spoke and disparaged Southern English at the same time. “Well, in the South we just talk like Rednecks here.” My second language teaching continued based upon conflicting viewpoints that I did not recognize at the time.

After teaching Spanish in the North Carolina public school system for over eight years, we moved to Baltimore, Maryland where I began graduate work. I received a Masters degree in Intercultural Communication at the University of Maryland Baltimore County (UMBC).

This field appealed to me, not only because of my own intercultural communicative successes and sometimes, drastic failures, but also because it offered a theoretical explanation to communicative differences.

Communication is negotiated through cultural, relational, and contextual lenses, all of which shape our assumptions of what we consider to be correct. This course of study began to unravel my standard language ideologies and give definition to discourse. My graduate work included intensive study of discourse: intercultural discourse, intercultural pragmatics, discourse analysis, language and gender, politeness theory, language and ethnicity, and language and power.

For my doctoral work, I drew upon this linguistic background and studied the relationship between student achievement and teacher’s attitudes toward their students who spoke African American English in inner city Baltimore. My research focused on the intricate process of how these teachers became linguistically aware and developed a model, Reframing a Linguistic Mindset (RLM, Strickling, 2020), that explains this process. After that, I completed a two-year post-doctoral position in Urban Education where I participated in evaluating the efficacy of Turnaround interventions in low performing schools in Baltimore. More specifically, I studied the language employed by members of Maryland’s Department of Education as they sought to build a rapport with principals and educational leaders from these inner city schools.

And I will end my linguistically autobiography right there for now.